In this installment of the Hidden Voices series, learn more about Maritcha Lyons, an educator and activist for many decades in New York City who dedicated her career to fighting for the rights of Black New Yorkers.

Hidden Voices began as a collaboration with the Museum of the City of New York that was initiated to help City students learn about the countless individuals who are often “hidden” from traditional historical records. Each of the people highlighted in this series has made a positive impact on their communities while serving as outstanding examples of leadership, advocacy, and community service.

Today, we're sharing the story of Maritcha Lyons, a lifelong educator and activist in New York City, who became one of the City's first Black assistant principals. Over the course of her career, Lyons was at the center of many of the nineteenth centuries most important civil rights fights.

Photograph of Maritcha Lyons as an adult. (Image Source: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, 1900).

Photograph of Maritcha Lyons as an adult. (Image Source: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, 1900).From her time growing up in a home that served as a stop on the Underground Railroad, to becoming the first Black student at her high school, and later, becoming an activist fighting for school desegregation, Maritcha Lyons (1848–1929) spent much of her life at the center of many of the nineteenth-century’s most significant historical moments. An educator and activist for many decades, Maritcha’s life in New York was spent fighting for the rights of her community, which she called home for most of her life.

Her parents, Albro and Mary Lyons, raised their children in Five Points, America’s original “melting pot” and the center of New York City’s Black population at the time, in a home located on what was once known as Vandewater Street, where they also ran boardinghouse for Black sailors. It was more than just the Lyons family home, however; the boardinghouse was also secret stop on the Underground Railroad. As the scholar Eric Foner describes it, the Underground Railroad “formed part of what Charles Sumner, the abolitionist senator from Massachusetts, called the ‘antislavery enterprise,’ the broad spectrum of individuals, outlooks, and activities devoted to bringing about the end of slavery.” It was not a single entity, or organized institution, but a series of local networks that helped fugitives reach safety in free states and Canada.

Though slavery had been illegal in New York State since 1827—just over 20 years before Maritcha’s birth on May 23, 1848—it was still a dangerous risk for anyone to help enslaved persons. This was partly because the State, particularly New York City, was still tied economically to the institution of slavery. Consequently, many local officials supported pro-slavery policies in the years leading up to the U.S. Civil War, and opposed abolition. The danger was compounded for abolitionists when, in 1850, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which required any enslaved person who had escaped bondage to be sent back to the South if they were captured in the North, while also enacting harsh punishments for anyone who assisted them in their quests for freedom.

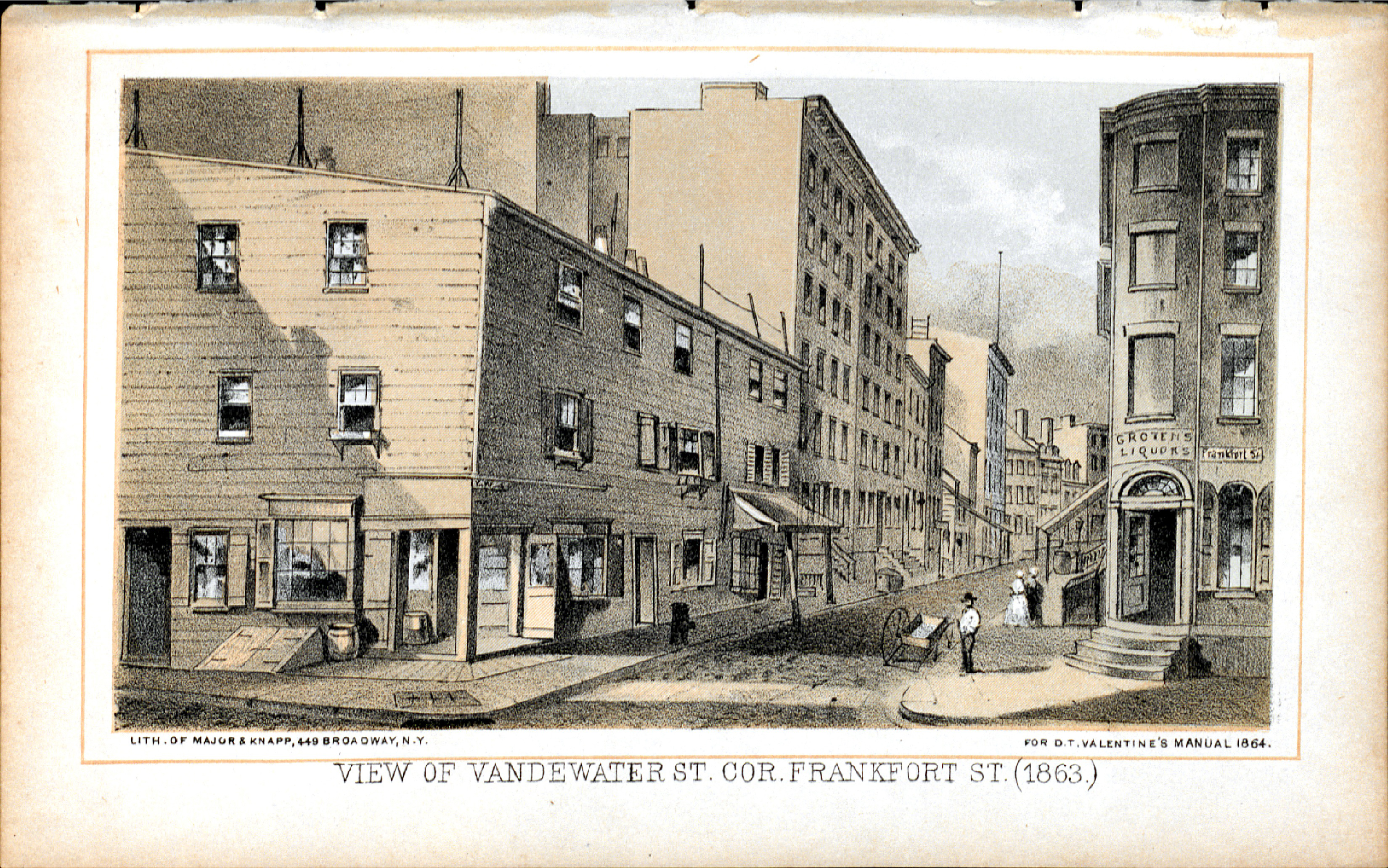

View of Vandewater Street in 1863. Today, Vandewater Street is closed, as it was partially covered by the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge before closing entirely with the construction of 375 Pearl Street and Murry Bergtraum High School in 1975. (Image Source: Major & Knapp, 449 Broadway, N.Y. Valentine’s Manual, Black Gotham Archive).

View of Vandewater Street in 1863. Today, Vandewater Street is closed, as it was partially covered by the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge before closing entirely with the construction of 375 Pearl Street and Murry Bergtraum High School in 1975. (Image Source: Major & Knapp, 449 Broadway, N.Y. Valentine’s Manual, Black Gotham Archive).

Fortunately, the Lyons’ boardinghouse provided a perfect cover for their abolitionist activities, as the men, women, and children seeking freedom were able to blend in with the travelers who typically went into and out of the boardinghouse every day. Thanks to the Lyons family’s bravery, along with many other “conductors” of the Underground Railroad like them, as many as 3,000 to 4,000 people escaping slavery are estimated to have been helped along their journey to freedom as they passed through New York City between 1835 and 1860.

While the boardinghouse on Vandewater Street was the home where Maritcha spent a majority of her early childhood, the Lyons family also held property in a neighborhood called Seneca Village prior to the 1850s. Seneca Village was located along what is now the perimeter of Central Park, from West 82nd to West 89th Streets, and was a place that many Black and immigrant families called home throughout the first half of the 19th century. However, in order to make room for the Park, the City forcibly took ownership over the area, and displaced the neighborhood’s residents. The Lyons family was no exception, as they lost their Seneca Village property when Maritcha was a very young child.

In spite of this, the Lyons family remained in New York, and after a period when she could not attend school due to an illness, Maritcha became a student at Manhattan’s Colored School No. 3 when she was 13 years old. Located on Broadway and 37th Street, it was there where Maritcha developed a “love of study for study’s sake.”

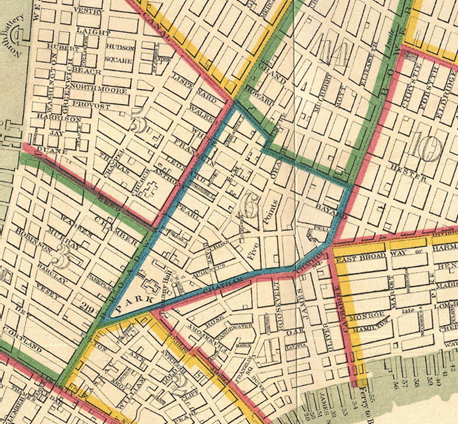

A section of a street map of New York from 1831 that outlines the neighborhood around Five Points in blue. (Image Source: Map of the City of New York Compiled and Surveyed by William Hooker, Wikipedia).

A section of a street map of New York from 1831 that outlines the neighborhood around Five Points in blue. (Image Source: Map of the City of New York Compiled and Surveyed by William Hooker, Wikipedia).

Unfortunately, though, by the time Maritcha was 15 years old, her family was forced to flee their home for their own safety, as their boardinghouse was repeatedly attacked during the July 1863 riots that erupted in New York City as the nation’s first military draft began.

The controversial conscription law had been passed and signed into law several months earlier—it required every male citizen and immigrant between the ages of 20 and 45 to register for a draft lottery and potentially enlist as soldiers in the Union army. However, the law also allowed the wealthy to buy their way out of military service altogether by paying a commutation fee of $300, or over $5,500 in today’s money. Moreover, the law did not include Black New Yorkers in the draft lottery pool, as Black Americans were still not considered U.S. citizens at the time.

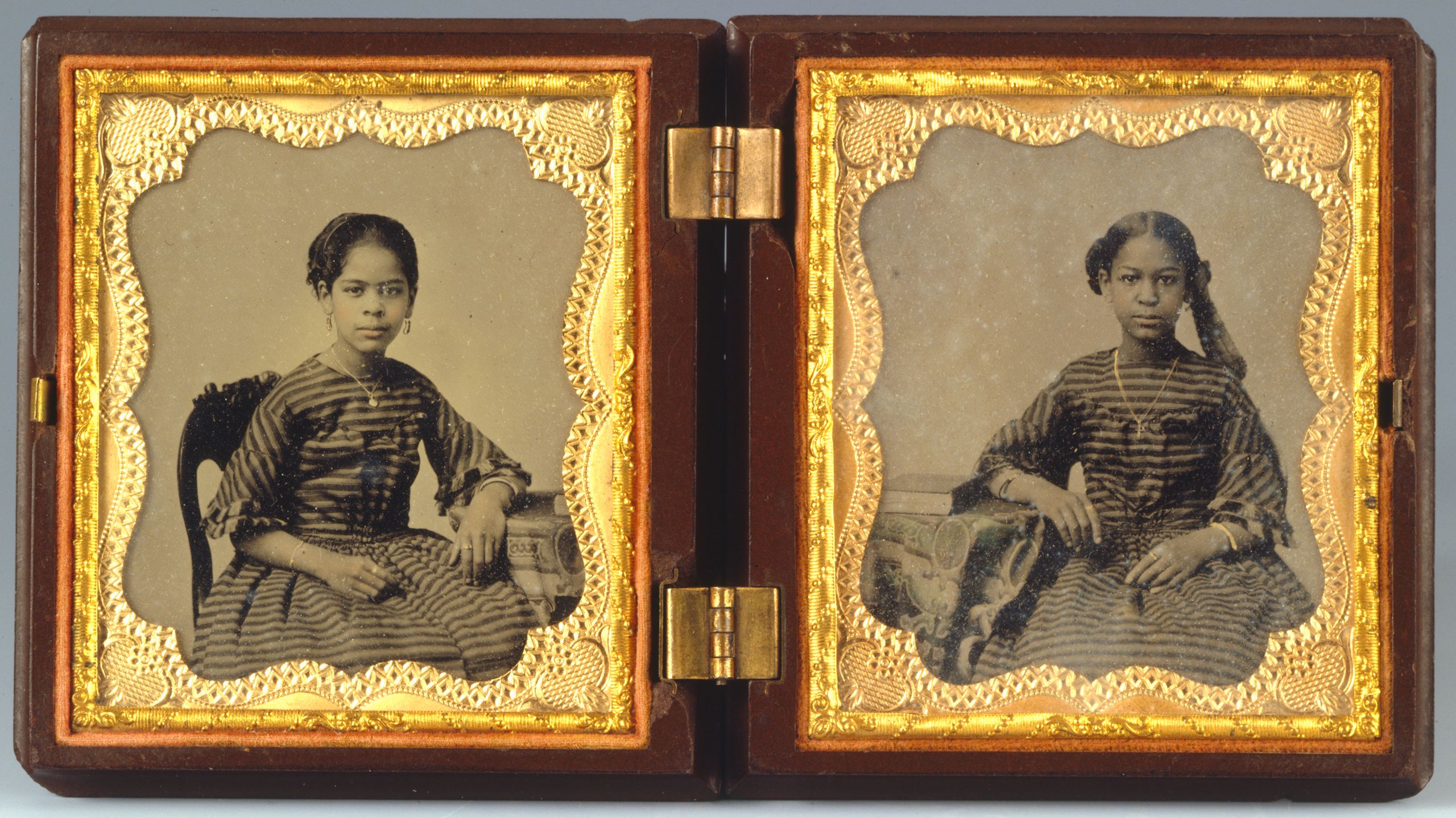

Portraits of Maritcha Lyons (left) and her younger sister Pauline (right) as children. Maritcha was the third of five children born to Albro and Mary Lyons. (Image Source: Schomburg Center For Black Research and Culture, NYPL).

Portraits of Maritcha Lyons (left) and her younger sister Pauline (right) as children. Maritcha was the third of five children born to Albro and Mary Lyons. (Image Source: Schomburg Center For Black Research and Culture, NYPL).

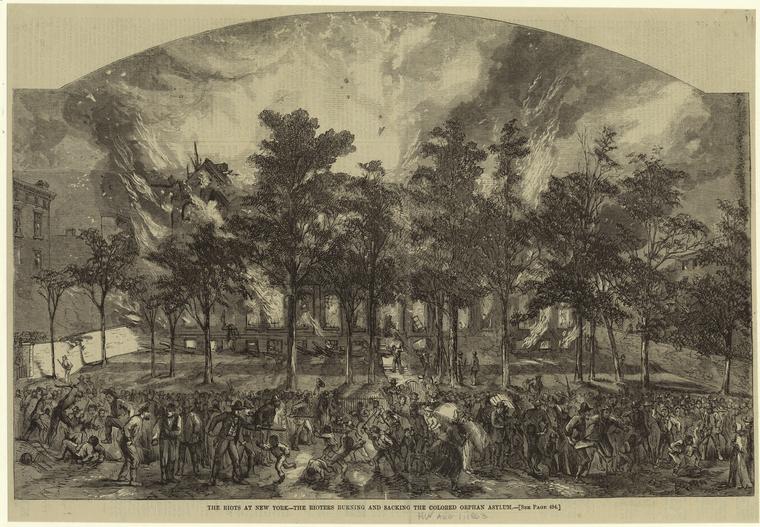

These exemptions led to fierce opposition to the draft law, especially among the City’s white, working-class poor, who would face the brunt of the impact of the draft law, and who subsequently directed their anger towards Black families and businesses. Mobs formed across the City, including in the Lyons’ neighborhood in Five Points. They sought to damage and destroy federal buildings and Black neighborhoods. The mobs’ anger seemed limitless—they had even burned and sacked the Colored Orphan Asylum, an orphanage for Black children. While the children and staff at the orphanage were fortunate to survive, most historians believe that around 115 people were killed over the course of the days-long rioting, including nearly a dozen Black freemen who were lynched.

During the height of the violence, the angry mob tried to break down the Lyons’ front door. The Lyons were lucky to escape with their lives; to keep his family safe, Maritcha’s father made the decision to escape with them to Providence, Rhode Island, where they would remain for several years.

The Colored Orphan Asylum was one of many buildings damaged during the New York City Draft Riots, during which the angry mob specifically targeted many Black families and businesses. (Image Source: The New York Public Library Digital Collections,1860).

The Colored Orphan Asylum was one of many buildings damaged during the New York City Draft Riots, during which the angry mob specifically targeted many Black families and businesses. (Image Source: The New York Public Library Digital Collections,1860).

While living in Providence, the Lyons family became leaders in the fight to desegregate the schools there. In fact, Maritcha became the first Black student to graduate from Providence Girls’ High School. Writing of her time there, she said “The iron had entered my soul. I never forgot that I had to sue for a privilege which any but a colored girl could have without asking.” This experience, along with the value of education that was instilled in her from a young age, undoubtedly shaped Maritcha’s future career path.

Maritcha’s first job was at Colored School No. 1—which was founded in 1827, after the African Free School was incorporated into the City of Brooklyn’s then-new public school system. The first African Free School was established in 1787, as part of the mission of the New York Manumission Society, and was “dedicated to providing tools of empowerment to young Black people.” This was an ambitious goal, and it was one that Maritcha shared.

Throughout much of her long career as an educator, she primarily worked in elementary education. At the time, this was the highest level of schooling that most children would receive, which was why Maritcha considered it to be “the education of the masses, not the classes.” Later, Maritcha became the assistant principal of P.S. 83 in Brooklyn, one of the city’s first fully integrated schools. Lyons was one of the first Black women to hold this role.

Lyons retired from her role as an educator in 1818 after 48 years, but her career as a teacher and principal was not where her work ended. By the 1890s, Maritcha had also become an activist alongside her work as an educator. She both worked alongside and debated the trailblazing journalist and activist, Ida B. Wells, raising funds for her anti-lynching campaign, and being a founding member of the Women’s Loyal Union of New York and Brooklyn. Through her work with this organization, she also helped to fight segregation in New York City’s schools and campaigned for women’s suffrage.

Maritcha died on January 28, 1929. Today, she is memorialized in New York City with both a city park and a public school named after her. As a beloved teacher and tireless advocate, Maritcha not only witnessed significant and historic change throughout her lifetime in the city she called home—she also played an active role in making those changes happen. She was an inspiring figure in her time, and remains an inspiration to civil servants, educators, and women alike to this very day.

Sources

Bolden, T. (2005). Maritcha: A Nineteenth-Century American Girl. Abrams.

Brisbon, L. D. (2018). Maritcha Remond Lyons. Alexander Street, Part II: Black Women Suffragists. https://documents.alexanderstreet.com/d/1007600765

Central Park Conservancy. (2018, January 18). Before Central Park: The Story of Seneca Village. Central Park Conservancy. https://www.centralparknyc.org/articles/seneca-village

Examination Days: The New York African Free School Collection. (2011). New-York Historical Society. https://www.nyhistory.org/web/africanfreeschool/history/index.html

Foner, E. (2015). Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of America’s Fugitive Slaves. Oxford University Press.

History.com Editors. (2009, December 2). Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. HISTORY. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/fugitive-slave-acts

Jacobs, J. (2019, October 20). Their Land Became Part of Central Park. They’re Coming Back in a Monument. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/20/arts/lyons-seneca-village-monument.html

Johnson, V. M. (2018). “The Half Has Never Been Told”: Maritcha Lyons’ Community, Black Women Educators, the Woman’s Loyal Union, and “the Color Line” in Progressive Era Brooklyn and New York. Journal of Urban History, 44(5), 835–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144217692931

Lakin Hutcherson, L. (2021, February 23). BHM: Good BlackNews Celebrates Ida B. Wells—Journalist, Anti-Lynching Activist, Women’s Rights Advocate. Good Black News. https://goodblacknews.org/tag/womens-loyal-union-of-new-york-and-brooklyn/

Major & Knapp, 449 Broadway, N.Y. Valentine’s Manual. (1864). “View of Vandewater Street, corner of Frankfort Street, 1863,” Lithograph. Black Gotham Archive. Retrieved from https://archive.blackgothamarchive.org/items/show/7/

Map of the City of New York Compiled and Surveyed by William Hooker. (1871). Five Points [Map]. Retrieved from https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:1831_Hooker_Map_of_New_York_City_(1871_reissue)_-_Geographicus_-_NewYork-hooker-1871.jpg

Maranzani, B. (2013, July 5). How the New York Draft Riots Became the Most Violent Insurrection in American History. HISTORY. https://www.history.com/news/four-days-of-fire-the-new-york-city-draft-riots

Maritcha Remond Lyons. (2023). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Maritcha_Remond_Lyons&oldid=1187528460#cite_note-14

Miller, S. C. (2022). Chapter 10: Dividing Bloomingdale, Seneca Village—The Black Leaders, 1825-1857. In Before Central Park. Columbia University Press.

Miss Maritcha Lyons, For 48 Years A Teacher in Brooklyn Schools, And a Militant Fighter for Women, is Dead. (1929, February 2). The New York Age, 1. Retrieved from https://basic.newspapers.com/image/40788737/

Overview, Colored School No. 1 Records, Sc MG 400, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. Retrieved from https://archives.nypl.org/scm/20890

Peterson, C. L. (2012, March 14). The Draft Riots of July 1863. The Black Gotham Archive. https://mith.umd.edu/news/the-black-gotham-digital-archive-the-draft-riots-of-july-1863/

Peterson, C. L. (2018, July 10). Maritcha Lyons. Black Gotham Archive. https://archive.blackgothamarchive.org/items/show/61/

Quits Teaching After 48 Years. (1918, July 20). The New York Age, 1–2. Retrieved from https://basic.newspapers.com/image/33453513/

Rozen-Wheeler, A. (2017, May 16). Maritcha Lyons (1848-1929). BlackPast. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/lyons-maritcha-1848-1929/

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. (1860). Maritcha Lyons and her younger sister Pauline. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/a7d0e925-f88a-eff6-e040-e00a18060357

Schomburg Center

for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York

Public Library. (1900). Maritcha Lyons Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/86ceccfb-3e62-d837-e040-e00a18064431

The New York Public Library. (1863). The riots at New York -- the rioters burning and sacking the Colored Orphan Asylum. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-280c-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99