In this installment of the Hidden Voices series, learn more about Dr. Joanne Chory, a Lebanese American plant geneticist whose early work revolutionized botany and who is now dedicated to the global fight against climate change.

Hidden Voices began as a collaboration with the Museum of the City of New York that was initiated to help City students learn about the countless individuals who are often “hidden” from traditional historical records. Each of the people highlighted in this series has made a positive impact on their communities while serving as outstanding examples of leadership, advocacy, and community service.

Today, in celebration of Arab American Heritage Month and Earth Day, we’re sharing the story of Dr. Joanne Chory, a Lebanese American plant geneticist whose early work revolutionized botany and who is now dedicated to the global fight against climate change.

What if plants could save the world?

Dr. Joanne Chory, a plant geneticist at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego, California, thinks that maybe they can.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1955 to Lebanese immigrant parents, Dr. Chory describes herself as a "late bloomer in science," who didn't even know what she wanted to study until taking a genetics course as an undergraduate at Oberlin College that would change the course of her life.

It was in the 1980s, as a postdoc at Harvard Medical School, when Chory first asked the question that would change the trajectory of her career: what if plants could grow and be healthy, all without any light? To find an answer to what might seem like an impossible question, she decided to conduct an experiment.

Dr. Chory planted thale cress seeds — a plant that very few scientists were studying at the time — into Petri dishes that were placed in an incubator and covered with foil to create dark conditions. However, these weren’t ordinary seeds: they had been soaked in a chemical that would damage their DNA in order to create mutations that might allow them to grow in the dark.

Dr. Joanne Chory in her lab (Photo Credit: Salk Institute)

Dr. Joanne Chory in her lab (Photo Credit: Salk Institute)

A week later, most of the seedlings were etiolated, which meant that they were weak, withered, and didn’t have any leaves. This wasn’t surprising; it’s how plants deprived of light are expected to grow. But, she noticed, a few of the seedlings did have leaves white in color, since as the plants were unable to produce chlorophyll in the dark) Other than their unusual color, these rogue seedlings looked just like a plant that had been growing out in the sun.

Chory and her team studied all of the genes known to be associated with light and found that they were “turned off,” as they would be in a normal plant. They later discovered the existence of a new light receptor related to the mutated gene—a revolutionary finding, and one that was first met with a lot of doubt and skepticism. She continued this work throughout the next decade, before joining the Salk Institute in 1988. By this point, she had expanded her research into a related genetic mutation in the thale cress plants, which led her to the discovery that plant hormones called bassinosteroids were also associated with the ways that the seedlings responded to light, and thus uncovering the entire pathway by which the hormones aid in plant development.

Today, Chory is a widely respected scientist: she has received many of top awards and honors throughout her career—including being elected to the U.S. National Academy of Sciences and receiving the Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences, among others. One of Chory’s collaborators, biologist Detlef Weigel, explained the significance of her findings on brassinosteroids: “If this discovery had been made not in the plant system, but in the animal system, it certainly would have been honored with a Nobel Peace prize” Another geneticist said that “Joanne is probably the most influential plant biologist of the modern era.”

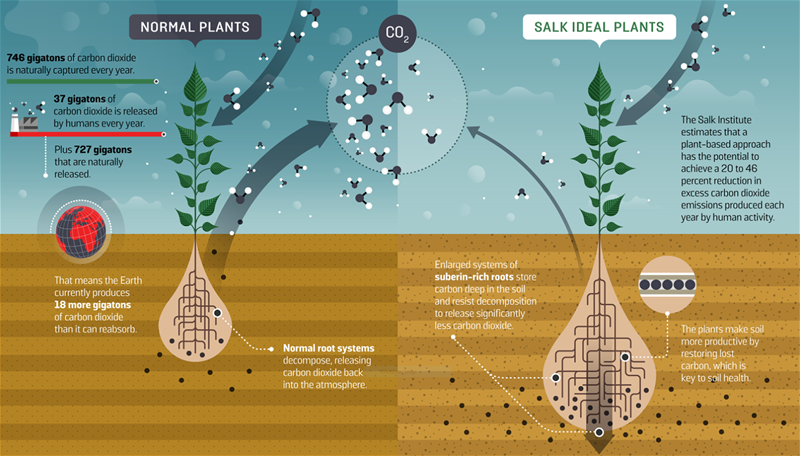

It’s easy to see why Chory has the respect of her peers; today, Chory and her team hope to use everything they’ve learned to create the ideal crops—stress-and pathogen-resistant perennials to help capture 20–50% more excess carbon dioxide in our atmosphere while also sustainably feeding the predicted 10 billion people who will inhabit the Earth by 2056.

This illustration shows the differences between normal plants and the “Ideal Plants” that are currently being researched at the Salk Institute. Ideal Plants are estimated to achieve a potential 20-46% reduction in excess carbon dioxide emissions produced by humans every year. (Photo credit: Foreign Policy/Salk Institute)

This illustration shows the differences between normal plants and the “Ideal Plants” that are currently being researched at the Salk Institute. Ideal Plants are estimated to achieve a potential 20-46% reduction in excess carbon dioxide emissions produced by humans every year. (Photo credit: Foreign Policy/Salk Institute)

In 2004, Dr. Chory was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease—but she hasn’t let that slow her down; today, she continues her plant research as the leader of the Salk Institute’s Harnessing Plants Initiative, which aims to fight climate change by “optimizing a plant’s natural ability to capture and store carbon and adapt to diverse climate conditions.” In other words, she and her team are working to create an “Ideal Plant,” that they hope will capture more CO2, and that will hold onto it for longer. Their plan is to genetically modify plant roots to be bigger, deeper, and contain more suberpin, a substance that can capture carbon and which is resistant to decomposition, in order to keep CO2 in the soil for much longer than is currently possible with normal plants. If these Ideal Plants are grown on a large scale, Chory believes they could suck enough carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere—she’s hoping for 10% of the 20 extra gigatons that humans release into the atmosphere, and which our ecosystem can’t currently handle on its own—to help slow down climate change.

She and her team still have a long road ahead of them before these superplants are widespread: even once why are successfully created, they will have to convince hesitant farmers to plant them and government regulators across the globe that the genetically-modified seeds are safe to use. But Dr. Chory remains hopeful: “We’re going to make plants better,” she once said of her work, “And we’re going to end up saving the world.”

Sources

Chory, J. (2019, April) “How Supercharged Plants Couls Slow Climate Change.” TED Talk. Available online: https://www.ted.com/talks/joanne_chory_how_supercharged_plants_could_slow_climate_change/transcript

Dreyfuss, E. (2019, April 26). “The Plan to Grab the World’s Carbon with Supercharged Plants.” WIRED. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/the-plan-to-grab-the-worlds-carbon-with-supercharged-plants/

Hook, L. (2019, January 31). “Could a New Superplant Solve the Climate Crisis?” Financial Times. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/aa055276-2419-11e9-8ce6-5db4543da632

Kaplan, S. (2021, April 28). “Joanne Chory is Harnessing Plants to Stop Climate Change.” The Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-solutions/interactive/2021/joanne-chory-climate-plants/

Landhuis, E. “Joanne Chory: Seeding the Field.” HHMI–An Inside Look. Available online: https://www.hhmi.org/insidelook/joanne-chory

Makowski, E. (2020, March 1). “Into the Light: A Profile of Joanne Chory.” The Scientist Magazine. Available online: https://www.the-scientist.com/profile/into-the-light-a-profile-of-joanne-chory-67141

Popescu, A. (2019, April 17). “This Scientist Thinks She Has the Key to Curb Climate Change: Super Plants.” The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/apr/16/super-plants-climate-change-joanne-chory-carbon-dioxide

Salk Institute for Biological Studies. “Scientist Directory: Joanne Chory, PhD.” Salk Institute for Biological Studies. Retrieved online from: https://www.salk.edu/scientist/joanne-chory/

Banner photo by Chris Keeney/Salk Institute. Original can be found online.